How does the economy work?

BY JAMES WILLIAMSON

In this blog we look at what drives an economy, what makes it boom or go bust, and why credit and debt are so important.

The human machine

An economy is the sum of all of its transactions - myriad exchanges of money or credit for goods or services. Transactions are driven by human nature, so an economy is in a sense a human transaction machine.

All cycles and forces in an economy are driven by transactions. Transactions for the same thing - like wheat, iPhones, shares, and so on - make a market. Transactions generate productivity growth and debt in an economy. The government is the biggest transactor in an economy. It collects taxes and spends money. The central bank controls credit (and debt), and the money supply.

source: Ray Dalio

A matter of trust

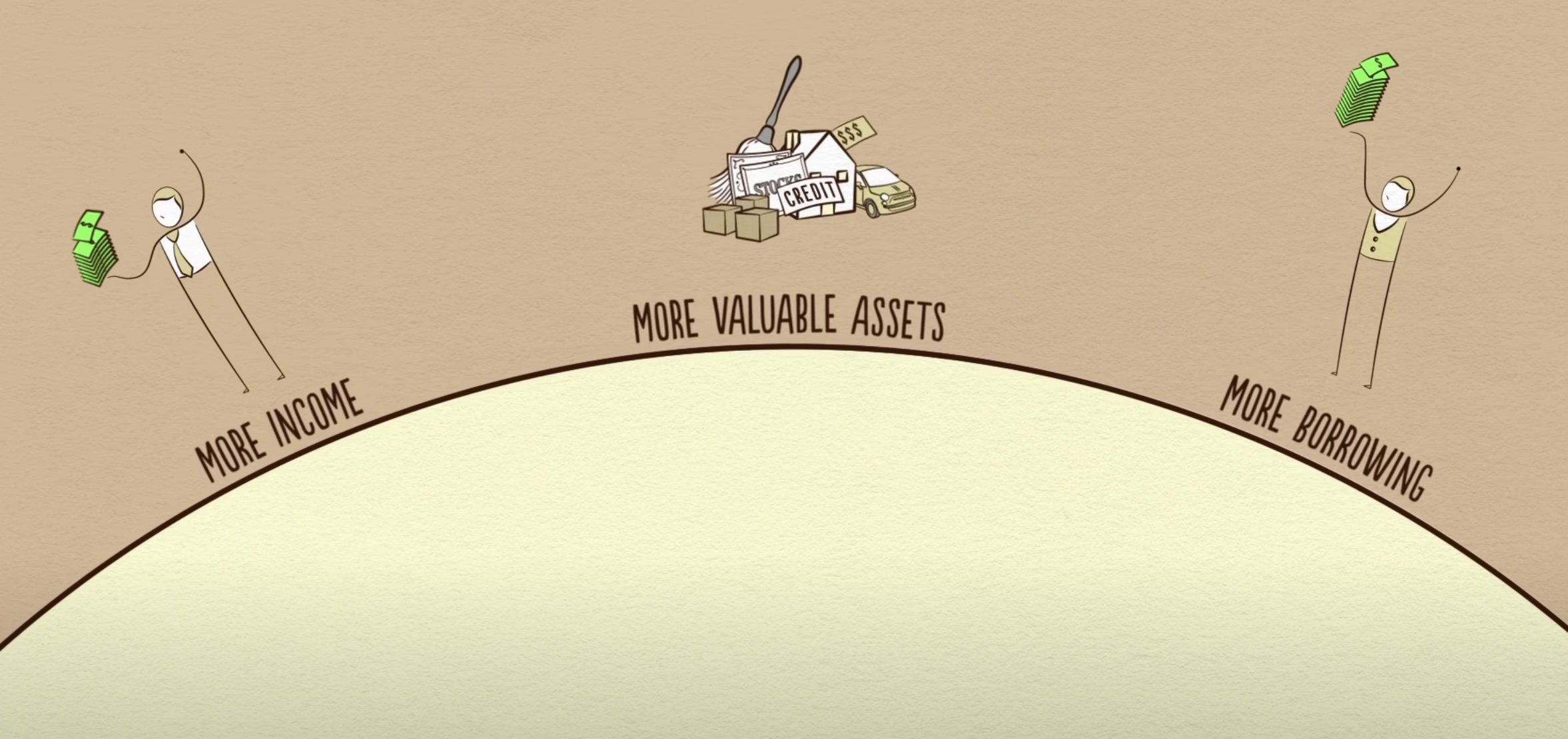

Money and credit drive spending, transactions and income in an economy.

Money is a medium of economic exchange. But credit is created. It comes from the Latin credere, which means ‘to believe’. The lender (creditor) believes the borrower (debtor) will faithfully repay the debt at a later date. It’s a matter of trust.

The principle is the amount loaned to the borrower. Interest is the additional amount charged for borrowing. Credit is expensive when interest rates are high, and there’s less borrowing. Credit cheaper when interest rates are low, and there’s more borrowing.

source: Ray Dalio

Credit is the biggest and most important part of an economy, and trust is crucial to an economy’s smooth functioning. When there’s more credit, typically there’s more spending and more income earned from the spending. The central bank controls money and credit by printing money and adjusting its official interest rate. We’ve seen this recently, where the Reserve Bank of Australia has hiked rates to reduce spending and lower inflation which at 6.1% annually is uncomfortably high for the RBA.

The flip side of credit is debt, which is crucial to productivity, income and prices.

“Credit is the biggest and most important part of an economy, and trust is crucial to its smooth functioning.”

Debt cycle and productivity

Borrowing creates debt cycles in the economy. This is the short term debt cycle. More lending, more spending and more income are self-reinforcing cycles that help generate economic growth.

How much income you get depends on how much you produce. Productivity growth matters most in the long run but credit growth matters most in the short run. Debt allows us to consume more than we produce when we acquire debt, and consume less than we produce when we pay the debt back.

Inflation and the debt cycle

Higher spending for the same quantity of goods and services drives up prices. This is called inflation.

When the central bank sees prices rising too fast, it raises interest rates to lower borrowing, reduce spending, thus lowering prices. This is called deflation. If economic activity falls, it is a recession. In a recession the central bank lowers interest rates to boost spending and borrowing as debt repayments are reduced. This is a credit expansion.

The short term debt cycle lasts for five to eight years. But each cycle ends with more growth and more debt because people tend to borrow more and spend more instead of paying back debt. This leads to higher inflation.

Boom or bust? The long-term debt cycle

Over time, debts rise faster than incomes. This creates the long-term debt cycle which leads to even more credit creation. Asset values are going up, the stock market is booming, and incomes seem to be rising. The economic boom seems to show that it pays to buy goods and services with borrowed money. The economic party can seem endless with the credit punchbowl at hand. But this is an illusion.

source: Ray Dalio

Why is the economic boom really an economic bubble? The reason is that there’s more debt than income in the economy. It is a debt burden. The problem is that, in a bubble, people feel wealthy so the debt burden doesn’t seem to be a problem. Borrowers remain creditworthy for a long time. But bubbles don’t last. Debt repayments rise over time and eclipse income growth, which forces people to spend less, in turn reducing incomes and borrowing. The debt cycle reverses and long term debt simply becomes too big.

“The economic party can seem endless with the credit punchbowl at hand. But this is an illusion.”

Dealing with deleveraging

This situation occurred in 2008 globally, in 1989 in Japan, and in 1929 in the US. In these times economies began to experience deleveraging.

Deleveraging is dangerous for an economy. Spending is cut, incomes fall, credit disappears, asset prices drop, banks get squeezed, and the stock market crashes. Squeezed borrowers are forced to sell assets, and a flooded market causes crashes in the stock or property market and banks are hit with rising mortgage defaults. Collateral dries up and people feel poor.

With low income, wealth, asset prices and credit growth, the deleveraging cycle can lead to an economic depression or collapse. The debt burden is simply too big to be resolved by ultra low interest rates. Lenders are not lending, borrowers are not borrowing, and the whole economy is effectively not creditworthy.

There are four main ways to deal with deleveraging. One, cut spending. Two, reduce debt. Three, redistribute wealth. Four, print money. These ‘levers’ have been pulled with every deleveraging in modern history with mixed results.

A beautiful deleveraging?

A ‘beautiful deleveraging’ balances economic policymaking correctly. It’s a virtuous cycle. Growth is slow but debt burdens go down. Incomes start to rise and borrowers appear more creditworthy. Lenders start lending more money and debt burdens finally start to fall. Rising spending and incomes get the economy growing again, leading to a reflation of the long-term debt cycle and and end to the deleveraging process. The process of reflation can take a decade or more for debt burdens to fall and economic activity to get back to normal.

Rules of thumb

An economy is simple in terms of how it works. But it is also complex as it involves humans making countless nuanced decisions. Ultimately, for an economy to grow steadily, incomes and productivity need to rise more than debt, particularly in a long-term debt cycle.

Three key things to take away from this blog are:

Don’t allow debt to rise faster than income - because your debt burdens will eventually crush you.

Don’t have income rise faster than productivity - because you’ll eventually become uncompetitive.

Do all you can to raise productivity - because this is what matters most in the long run.

This article draws from Ray Dalio’s video: ‘How the economic machine works’